RLM-on-KG: Recursive Language Models and the Future of SEO

Recursive Language Models (RLMs) treat prompts as environments to explore, not consume. We adapted this for Knowledge Graphs and discovered why structure, not bigger context windows, is the key to AI accuracy and search visibility.

We are entering a new phase of the web, what I call the Reasoning Web. And with it comes a turning point for search as we’ve known it. AI systems are no longer passive readers of documents; they’re becoming agents that explore information spaces, navigate relationships, and build understanding through structured reasoning.

That distinction matters.

Retrieval‑augmented generation (RAG) grounded LLM outputs by injecting external sources into prompts. But most RAG systems still behave like a single lookup: one query, top chunks, one synthesis. This works when the answer lives in a single passage. It fails when the truth emerges only from the connections between pages, entities, and concepts.

And enterprise questions rarely fit in one page.

When Zurich Insurance asks about coverage options that span multiple policy types, the answer isn’t “in an article.” It’s in the structure, policy definitions, exclusions, jurisdictions, endorsements, and in how they relate. When an automotive transport customer wants to know how routes affect pricing, the answer emerges from the interplay of locations, constraints, seasonal demand, carrier availability, and service tiers.

In other words: the evidence lives in the graph, not just the text.

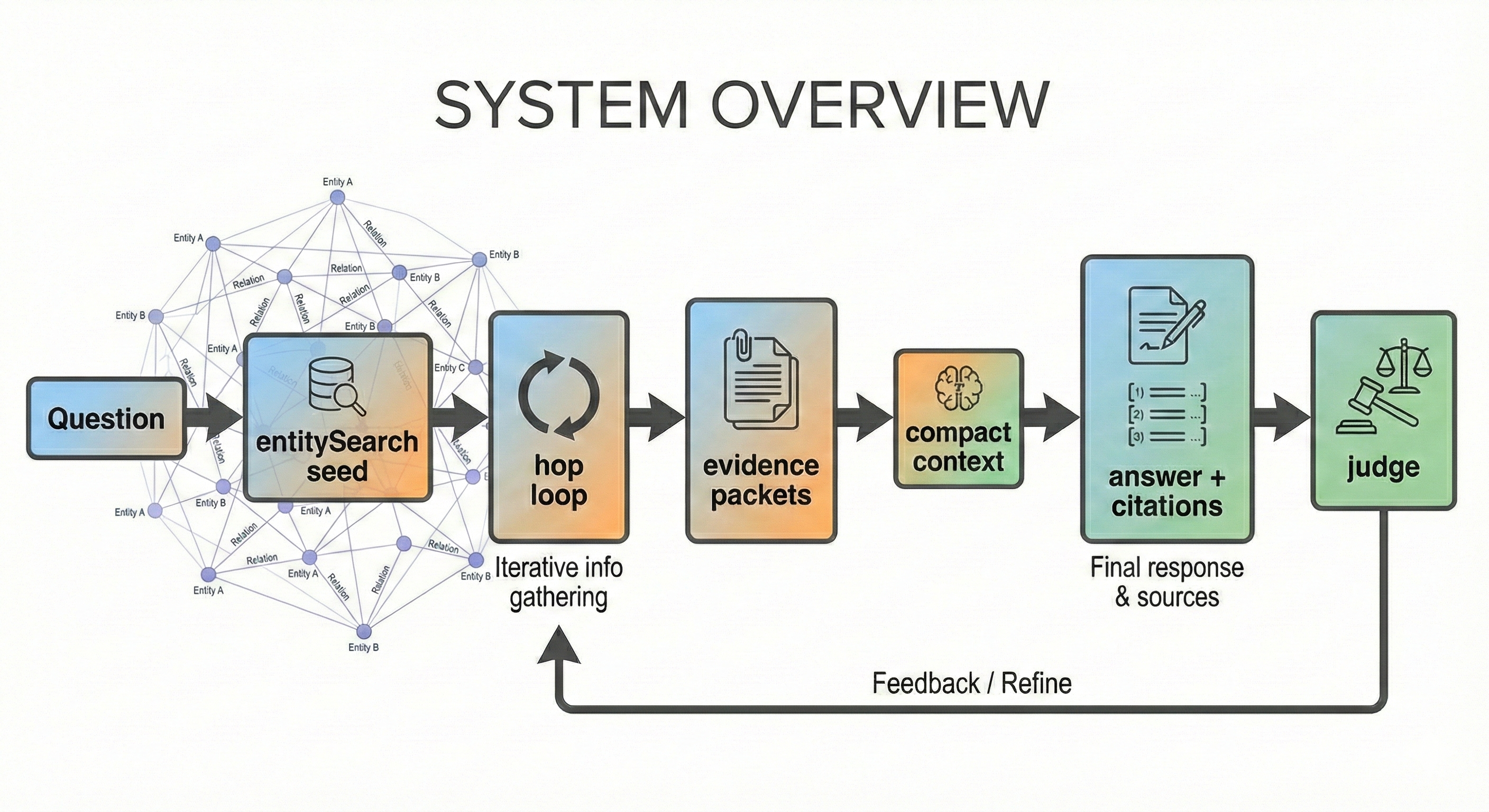

This article introduces RLM‑on‑KG, an adaptation of recursive language model inference where the “environment” is a WordLift Knowledge Graph accessed via GraphQL. Recursive Language Models (RLMs), introduced in recent research by Alex Zhang, Tim Kraska, and Omar Khattab at MIT (arXiv), propose a simple but powerful idea: instead of feeding massive amounts of context into a language model and hoping it stays coherent, let the model treat the prompt as an external environment it can inspect, decompose, and navigate recursively.

Using a 150‑question benchmark built from a WordLift blog knowledge graph (Articles + FAQPages), we compare three answering modes, Vanilla, Simple RAG, and RLM‑on‑KG, and surface two key findings:

- Multi‑hop KG traversal improves evidence quality and citation behavior.

- It also reveals a failure mode, overreach, visible only when we add an explicit grounding judge.

1. Introduction

1.1 Motivation: SEO in the era of “infinite context”

Modern SEO is increasingly about semantic coverage: entities, relationships, structured data, and satisfying user intent across an interconnected content network. For an LLM agent, “infinite context” is not a massive prompt, it’s a large, evolving corpus of linked knowledge. The central challenge becomes:

How do we turn unlimited context into navigable memory with provenance?

In the Reasoning Web, SEO shifts from optimizing individual pages to optimizing signals for reasoning.

We’re entering a world where AI systems:

• explore content across multiple steps

• follow entity relationships

• verify claims across sources

• build answers by navigating structure, not by reading a single page

The guiding question becomes:

Is your content explorable by reasoning systems?

If your site is well‑structured, with semantic markup and explicit entity relationships, AI agents can traverse it deeply. They can connect ideas across pages, disambiguate meaning, and construct accurate answers.

If your site is mostly unstructured text, the agent sees isolated fragments. It can retrieve, but it cannot navigate.

This is the shift toward what I call SEO 3.0: optimizing your information architecture so AI agents can explore it intelligently, not just retrieve it superficially.

1.2 From RLMs to RLM-on-KG

The RLM framework, introduced by Zhang, Kraska, and Khattab at MIT, in December 2025 flips the script as it reframes the memory problem (I wrote about the paper, here on LinkedIn).

Instead of shoving more information into the context window, let the model explore its environment recursively, querying, examining, and decomposing information step by step.

Think of it as the difference between:

- giving someone ten random pages and asking them to answer a question

vs. - letting them roam an entire library, follow references, and build an understanding iteratively.

RLMs treat the prompt as an external environment they can navigate, implemented as a Python REPL in the original paper.

I asked myself a simple question:

What if that environment was a Knowledge Graph?

Recursive Language Models (RLMs) treat long prompts as an environment and allow the LLM to programmatically examine, decompose, and recursively call itself over snippets.

I made one extra step:

If the environment is a knowledge graph, then “infinite context” becomes a graph exploration problem.

Along with the team, we adapted the RLM approach by replacing the Python REPL with something we know intimately: a WordLift Knowledge Graph accessed via GraphQL.

In the implementation, the model doesn’t receive a massive context dump. Instead, it navigates the graph iteratively. Each “hop” brings back thin evidence, a few FAQs, some article snippets, key entity relationships, typically around 200 bytes rather than 50KB articles.

The model (Gemini Flash 3.0) examines this evidence, decides which related entities to explore next, and continues until it has enough perspective to synthesize an answer. Here is in short:

- Fetch a node (seed entity)

- Pull a tiny subgraph (neighbors via KG relations / co-occurrence in content)

- Recurse with a hop budget

- Synthesize an answer while citing URIs/URLs observed during traversal

The navigation isn’t random. It’s guided by question relevance, how well each entity matches the original query, and diversity, ensuring the model explores different angles rather than drilling into one perspective.

1.3 Positioning vs GraphRAG

GraphRAG (as introduced by Microsoft) builds a graph index from raw text, then uses community summaries and query‑time retrieval to answer questions at scale, particularly well suited for global, corpus‑level queries.

RLM‑on‑KG differs from GraphRAG in three practical ways:

1. Graph source

• GraphRAG: constructs a graph from documents.

• RLM‑on‑KG: operates on a native, pre‑curated RDF knowledge graph with explicit semantic relationships.

2. Query‑time behavior

• GraphRAG: retrieves communities/summaries to assemble an answer.

• RLM‑on‑KG: runs a multi‑hop exploration policy where traversal itself is the primary reasoning loop.

3. Provenance granularity

• GraphRAG: citations generally point to text chunks or community summaries.

• RLM‑on‑KG: cites specific entity URIs and page URLs discovered hop‑by‑hop (e.g., Article and FAQ URLs), which aligns more naturally with SEO needs such as traceability and editorial review.

2. System: WordLift KG as an environment

2.1 WordLift KG access

We use WordLift’s GraphQL endpoint to query an account/site knowledge graph.

The key capabilities are:

entitySearchfor semantic/lexical discovery of candidate entitiesresource(iri:)for schemaless access to node properties and relations- Article/FAQ retrieval patterns that return URLs + content snippets

For more context on WordLift KG concepts and API usage, see docs.wordlift.io.

2.2 Evidence types

Our blog KG is organized around:

- Articles (e.g., schema:Article / headline, description, url)

- FAQPages with Q/A pairs (schema:FAQPage, schema:mainEntity, schema:acceptedAnswer)

- Entities connected via schema relations (e.g.,

schema:about,schema:mentions)

3. Methods

To evaluate the approach, we built a 150‑question benchmark from the WordLift blog knowledge graph (Articles + FAQPages). We compared three answering modes:

1. Vanilla: Gemini Flash 3.0 answers directly from training data. No retrieval. Fast but with no provenance.

2. Simple RAG: single‑shot retrieval: search once, retrieve top results, and synthesize.

3. RLM‑on‑KG: multi‑hop traversal of the knowledge graph, aggregating evidence from five entities across five hops before synthesis.

3.1 Compared answering modes

Mode A — Vanilla

LLM answers directly with no retrieval. Produces fluent responses but no provenance.

Mode B — Simple RAG (one-shot)

entitySearch(question)- Pick top entity

- Fetch top FAQs + top Articles (thin snippets)

- Answer using only that evidence

Mode C — RLM-on-KG (multi-hop)

- Seed entity from

entitySearch(question) - For each hop (budget = 5):

- gather an EvidencePacket for focus entity (FAQs + article snippets)

- expand candidates using related entities from top articles (

schema:about+schema:mentions) - choose next entity via a simple overlap-plus-score policy (avoid revisiting)

- Build a compact context from evidence packets

- Generate answer constrained to evidence and asked to cite URLs when possible

3.2 The exploration loop as a policy

We can formalize RLM-on-KG as a lightweight Markov Decision Process (MDP):

- State: current focus entity (IRI/name), visited set, hop index

- Actions: select next entity among neighbors/candidates

- Transition: next entity becomes focus

- Budget: fixed hop limit

- Objective: maximize downstream grounded answer quality (approximated by our judge)

4. Evaluation and Learnings

What We Learned: Evidence, Citations, and a Failure Mode Worth Studying

RLM-on-KG gathered 4-6x more evidence than simple RAG. It discovered connections that didn’t exist in any single article, relationships that only become visible when you follow the graph structure from entity to entity.

When asked about semantic SEO, for example, the system didn’t just return articles tagged with that term. It hopped to Knowledge Graphs, then to Structured Data, then to Schema.org, accumulating evidence at each step. The final synthesis showed how semantic SEO is built on knowledge graph principles, a relationship no single document stated explicitly.

The multi-hop approach also improved citation behavior. Instead of relying on one or two sources, answers drew from diverse perspectives across the graph.

But we also discovered a failure mode that deserves attention: overreach.

When we introduced an explicit grounding judge to evaluate answers, we found cases where the system achieved high intent coverage, it addressed what the user asked, but with low faithfulness to what the evidence actually supported. The model was sometimes confident about conclusions the underlying sources didn’t quite warrant.

This becomes visible only when you add rigorous grounding evaluation. Without a judge checking faithfulness, the answers look impressive. With one, you see where enthusiasm outpaced evidence.

We think this is critical for anyone building AI systems that need to be trustworthy. The structure gives you more material to synthesize, which is powerful, but that same richness can enable more sophisticated hallucinations if you’re not careful.

4.1 Dataset

- 150 questions (blog FAQ-style prompts)

- For each question: 3 answers (Vanilla, Simple RAG, RLM-on-KG)

- Total: 450 rows (150 questions × 3 modes)

4.2 Grounding judge

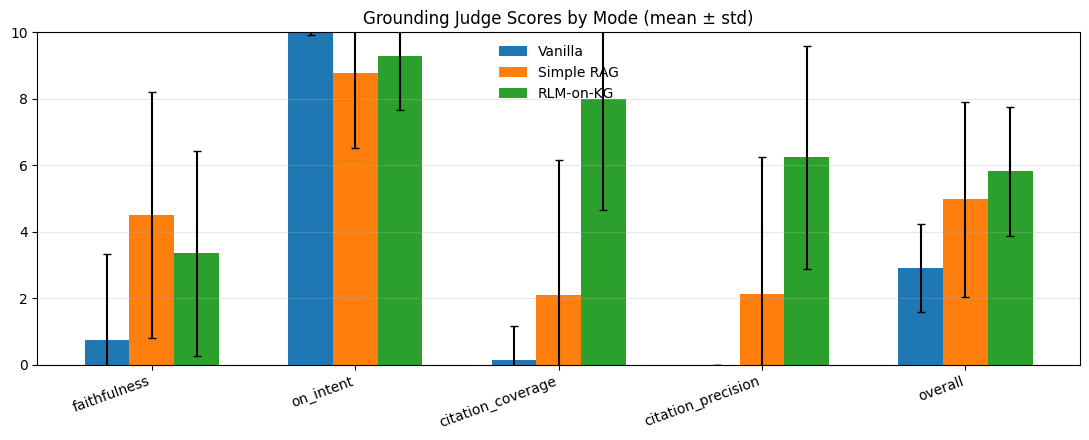

We use an LLM-based evaluator that outputs structured scores:

faithfulness(0–10): are claims supported by evidence?on_intent(0–10): does it answer the question?citation_coverage(0–10): are key claims cited?citation_precision(0–10): are cited URLs among allowed sources?

Important limitation: Vanilla has no retrieval → “allowed sources” and “evidence” are absent, so the judge tends to score its faithfulness/citations near zero by design. This is useful for “grounding compliance,” but it is not a fair factuality comparison unless Vanilla is also provided evidence for evaluation.

4.3 Mean scores (± std)

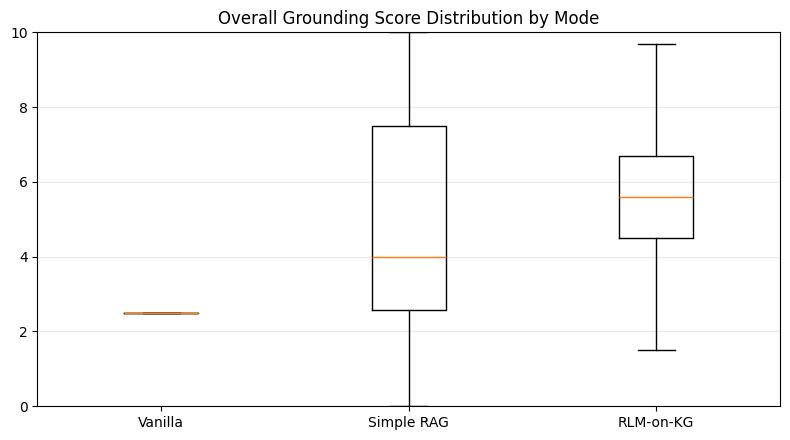

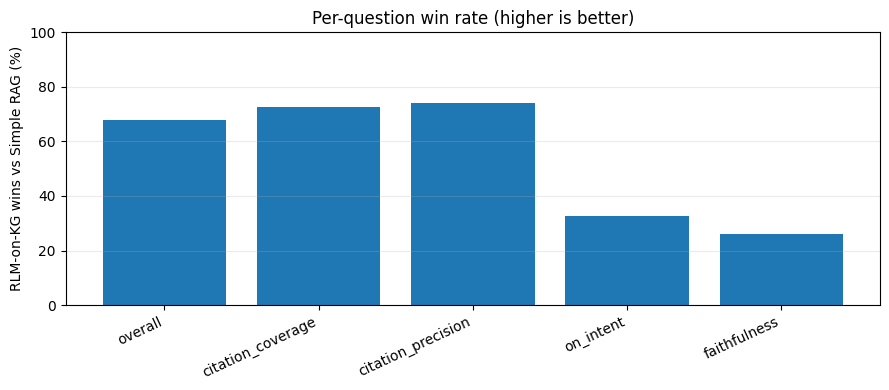

For each metric, we compute the percentage of questions where RLM-on-KG’s score exceeds Simple RAG’s score (ties excluded or reported separately, depending on the analysis). RLM-on-KG wins most often on citation coverage and citation precision, and wins a majority of questions on the overall score, while losing more frequently on faithfulness, highlighting a tradeoff between improved citation behavior and increased risk of overreach during multi-hop synthesis.

Here is the summary:

| Mode | overall | faithfulness | on_intent | citation_coverage | citation_precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RLM-on-KG | 5.813 ± 1.947 | 3.347 ± 3.096 | 9.273 ± 1.601 | 7.987 ± 3.328 | 6.233 ± 3.363 |

| Simple RAG | 4.981 ± 2.932 | 4.513 ± 3.698 | 8.780 ± 2.273 | 2.107 ± 4.064 | 2.133 ± 4.110 |

| Vanilla | 2.897 ± 1.325 | 0.753 ± 2.567 | 9.993 ± 0.082 | 0.147 ± 1.013 | 0.000 ± 0.000 |

Interpretation:

- RLM-on-KG strongly improves citation behavior (coverage + precision) versus Simple RAG.

- RLM-on-KG improves overall versus Simple RAG.

- Simple RAG has higher faithfulness than RLM-on-KG under this judge setup—suggesting a meaningful failure mode (overreach).

4.4 Paired deltas (RLM-on-KG − Simple RAG)

The paired analysis between RLML-on-KG and Simple Rag shows:

- Overall: +0.832 (95% CI ≈ +0.351 to +1.297), Cliff’s δ ≈ 0.40, Wilcoxon p ≈ 4.17e-05

- Citation coverage: +5.88 (CI ≈ +4.94 to +6.80), δ ≈ 0.59, p ≈ 6.97e-18

- Citation precision: +4.10 (CI ≈ +3.13 to +5.05), δ ≈ 0.59, p ≈ 3.15e-10

- On-intent: +0.493 (CI ≈ +0.10 to +0.893), δ ≈ 0.153, p ≈ 2.56e-02

- Faithfulness: −1.167 (CI ≈ −1.747 to −0.593), δ ≈ −0.20, p ≈ 2.04e-04

Let’s review an example from the dataset related to the question “How does Knowledge Graph-Native content work?”

| mode | answer |

| Simple RAG | Knowledge Graph-Native content works by using connected entities to build a “web of interconnected meanings.” It combines a knowledge graph approach with JSON-LD representation and structured data—such as taxonomies and schemas—to make content modular, findable, and portable. This structured approach allows content to be easily reproduced in different formats or moved between databases. Additionally, it involves creating content through “intelligent entity AI SERP analysis.” |

| RLM-on-KG | Knowledge graph-native content works by connecting entities to build a “web of interconnected meanings.” According to the provided evidence, the process involves several key components: * **Interconnected Entities:** The core of the approach is the use of entities that work more effectively when they are connected, reflecting a vision of the web based on shared meanings (https://wordlift.io/blog/en/knowledge-graph-native-structured-content/). * **Structured Data and JSON-LD:** Content is represented using JSON-LD. This structured data approach makes content modular, allowing it to be easily reproduced in different formats, moved between locations, or populated into various databases (https://wordlift.io/blog/en/knowledge-graph-native-structured-content/). * **Intelligent Analysis:** Creation of this content involves “intelligent entity AI SERP analysis,” often utilizing tools like SEO add-ons to bridge traditional SEO with advanced AI functionalities (https://wordlift.io/blog/en/knowledge-graph-native-structured-content/, https://wordlift.io/blog/en/knowledge-graphs-ai-powered-seo/). * **Findability and Portability:** By using taxonomies and schemas, the content becomes more findable for search engines and can be easily picked up by personal digital assistants like Google Assistant (https://wordlift.io/blog/en/knowledge-graphs-ai-powered-seo/, https://wordlift.io/blog/en/make-your-website-talk/). * **Data Integration:** In specific contexts like e-commerce, it involves transforming product feeds (Merchant or Manufacturer feeds) into a product knowledge graph to improve visibility in search results (https://wordlift.io/blog/en/how-build-product-knowledge-graph/). |

Simple RAG (single-pass)

- Citation coverage: 0

- Citation precision: 0

- Faithfulness: 3

- On-intent: 10

- URLs in answer: 0

- Judge note (summary): the answer was plausible, but not grounded/cited and only weakly supported by the retrieved evidence.

RLM-on-KG (recursive graph exploration)

- Citation coverage: 10

- Citation precision: 10

- Faithfulness: 10

- On-intent: 10

- URLs in answer: 6

- Judge note (summary): the answer accurately described the concept and key claims were supported by the allowed sources.

RLM-on-KG increases “grounded behavior” (citations + coverage) and improves overall score, but it currently pays a faithfulness penalty vs one-shot RAG.

What This Means for SEO

Let me translate these findings into the language of search and discovery.

Infinite context isn’t the answer. The industry has spent years racing toward larger context windows, assuming that more input means better output. Context rot research, and our own experiments, suggests this assumption breaks down. What matters isn’t how much context you can theoretically provide, but how efficiently an AI system can navigate to the relevant pieces.

Structure becomes the key to accuracy. When the environment is a knowledge graph rather than raw text, the AI has navigation affordances. It can follow typed relationships, query specific entity properties, and traverse connections intentionally. This structure improves both retrieval quality and synthesis accuracy, because the model isn’t just finding text that pattern-matches the query, it’s understanding how concepts relate.

We can now measure AI-readiness of structured data. Traditional SEO metrics, rankings, impressions, click-through rates, measure visibility to search engines. But as AI agents become the primary consumers of online information, we need new metrics. By observing how an RLM navigates a knowledge graph, we can identify which entities are well-connected, which relationships enable productive reasoning, and where structural gaps limit discovery.

At WordLift, we’re calling this SEO 3.0: optimizing not for traditional search algorithms but for AI agents that reason over structured information. RLM-on-KG gives us a way to actually measure how that reasoning works, and where it fails.

The Path Forward

RLMs are still new. The original paper focuses on synchronous sub-calls with a maximum recursion depth of one, and explicitly notes that deeper recursion and asynchronous approaches remain unexplored. The authors hypothesize that RLM trajectories can be viewed as a form of reasoning that could be trained explicitly, just as reasoning is currently trained for frontier models.

I am inclined to agree. The combination of structured environments and recursive navigation feels like a natural fit for the next generation of AI agents, systems that don’t just respond to queries but actively explore knowledge spaces to build comprehensive understanding.

For those of us building knowledge infrastructure, this research validates a core thesis: the web of tomorrow isn’t just about content, it’s about connections. The sites that structure their information as navigable graphs, with explicit relationships, typed entities, and semantic annotations, will be the sites that AI agents can reason over effectively.

The sites that remain unstructured blobs of text, however search-engine-optimized, will suffer from the same context rot that plagues today’s RAG systems.

Structure isn’t just nice to have. In an AI-first world, it’s the foundation for being understood at all.

References

- Zhang, A. L. et al. “Recursive Language Models.” arXiv (2025). (arXiv)

- Edge, D. et al. “From Local to Global: A Graph RAG Approach to Query-Focused Summarization.” arXiv (2024). (arXiv)

- Microsoft Research. “Project GraphRAG.” (Microsoft)

- WordLift. “GraphQL support / Knowledge Graph documentation.” (docs.wordlift.io)

- WordLift. “Content Evaluations API / Agent workflow.” (docs.wordlift.io)